It won’t make any difference because…

The National Advisory Council of a prestigious west coast business school was asked what single quality they thought would be most valuable for their graduates to acquire as they graduated. The answer was self-awareness.

For us, the most important element of self-awareness, especially for those who lead organizations, is a clear understanding of the impact they are having on the people around them.

What’s the key to unlocking potential?

Every organization contains pockets of great performing teams, but interestingly, no discernible difference exists in the basic know-how of the good performers versus the great performers. The key differentiators boil down to two things great performers have been coached to do: execute well and concentrate on reducing inconsistency in bad behavior.

The best predictor of future performance is mostly determined by past performance. Identify the existing islands or pockets of excellence within an organization. To leverage top performance, leaders should find out what the top performers or high-performing teams are doing to produce high-quality results. Leaders must not only capture their strategies but uncover the key competencies, the new and better behaviors, and the attitudes of those who are fully engaged. Using examples and stories of what excellence looks like can inspire and educate others.

Ask team members how they can improve their strategic performance, and then provide feedback and support. Establish an environment in which leaders are trained to coach individuals and teams in ways that build upon their strengths and passions. If an individual or a team is stuck, talk about the problems, give appropriate feedback, and address options and opportunities, rather than allow the issues to fly under the radar. The way forward is to name it, reframe it, and provide support to improve it.

Be competitive or achieve success?

How to garner extraordinary buy-in!

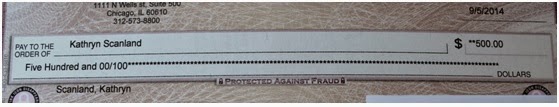

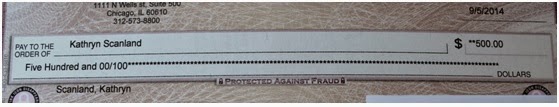

Now and then I experience something personally that I just have to blog about, and this is one of those instances. Sunday, the extraordinary happened. Way back in 1978, my church, along with three other churches, invested in a mixed-income housing project across the street. It was important to these churches to provide affordable and mixed-income housing options in what was then a neighborhood close to Cabrini Green. This property is now being re-developed and the churches sold their portion to the developers (with the requirement that it would include even more affordable housing options) and we received our portion of that sale, which was $1.6 million! But wait, that isn’t the extraordinary.

Now and then I experience something personally that I just have to blog about, and this is one of those instances. Sunday, the extraordinary happened. Way back in 1978, my church, along with three other churches, invested in a mixed-income housing project across the street. It was important to these churches to provide affordable and mixed-income housing options in what was then a neighborhood close to Cabrini Green. This property is now being re-developed and the churches sold their portion to the developers (with the requirement that it would include even more affordable housing options) and we received our portion of that sale, which was $1.6 million! But wait, that isn’t the extraordinary.