Organizations over-focus on managing the present—increasing efficiencies—and they think they are doing strategy. ~Vijay Govindarajan

Over the years, I have had individuals argue during discussions about strategic planning that “getting better” is strategic. Getting better, making improvements is absolutely something that needs to happen in organizations and it certainly should be encouraged. However, I still believe “getting better” isn’t strategy.

Over the years, I have had individuals argue during discussions about strategic planning that “getting better” is strategic. Getting better, making improvements is absolutely something that needs to happen in organizations and it certainly should be encouraged. However, I still believe “getting better” isn’t strategy.

Several years ago I heard Vijay Govindarijan speak about The Innovation Challenge. This week his presentation came to mind as I was working on a project in health care. I reviewed his presentation once again and still believe his premise that strategy is innovation.

VG (as he’s called) says that organizations spend time and resources in three boxes. If there is an over-focus on Box 1, innovation may never occur.

Box 1: Managing the present = efficiency

Box 2: Selectively forgetting the past = what you will abandon

Box 3: Creating the future = innovation

Therefore, strategy is answering the question: How do we create the future while managing the present?

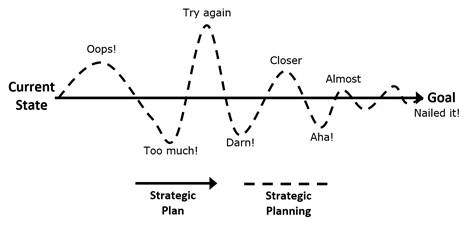

I think this is why so many strategic plans fail. The plans weren’t strategic in the first place. In other words, they focused on managing the present, got more efficient, but nothing new emerged. Or, they got frustrated by the enormous challenge of creating the future while managing the present, and essentially gave up.

VG maintains that you can’t create strategy in your dominant logic. Your dominant logic (performance engine) is the kind of people you hire, the kind of processes you have, the performance measures you monitor, etc. All of this is needed for continued operational execution (i.e., efficiency), but it is also a barrier to innovation, or strategy.

How do you simultaneously do innovation and efficiency? That’s strategic planning. And, that’s hard.

According to VG, there are two common innovation killers.

- To assume that innovation can happen inside the dominant logic (your current performance engine).

- The innovation team and plan is not constituted correctly. It has to be a separate team and plan with different responsibilities. In other words, not the operational team. You may need to recruit people from outside of your organization because you are building new capabilities and selectively forgetting some of what’s worked in the past.

There’s far more to unpack around this topic. But if your strategic planning isn’t going anywhere, maybe part of the reason is because the very same team is trying to both manage the present (operational efficiency) and create innovation (strategy). Step 1: Start your strategic planning by building a dedicated team to create the future and function without the restrictions of your current dominant logic.